|

I recently created a Website for my Public History Class at CUNY GC:

https://choncholi.weebly.com/ It’s the story of “choncholi se va pal monte” a refrain or estribillo that was used before and during Cuba’s Ten Years War by Black residents of #loshoyos in #SantiagodeCuba .

0 Comments

This post will deal with “Conga Fusion” recordings, which I define as commercial releases that combine substantial elements of both conga santiaguera (referred to as “conga” here) and other musical styles. (Download the PDF for easiest reading with working links!) Conga-Descarga: The 1950 (?) Panart Session Strangely enough, the first “fusion” recording is also probably the oldest known recording of conga santiaguera. “Conga en Oriente/Goza Mi Conga,”described in detail here, combines the conga “groove” or rhythmic feel, corneta china, and acoustic piano and bass. Conga-Jazz: New York, France and back to Santiago In 1983, percussionist Daniel Ponce (1953--2013), who arrived on the 1980 Mariel boatlift, recorded Ernesto Lecuona’s “Siboney” to a conga groove. Ponce had performed with carnival comparsas in his native Havana and was probably familiar with the Santiago style. This track features Paquito D’Rivera soloing on sax and a minimal percussion section of agogô bells and bass drums. "Siboney" refers to one of the indigenous tribes that inhabited Cuba before the arrival of the Spanish colonists and acts as a symbol for the island. It is also the name of a town near Santiago. This track is significant because it is probably the first conga santiaguera recording made outside of Cuba; this groundbreaking album was Ponce’s first recording as a bandleader. Ponce’s aggressive but tasteful tumbadora (“conga drum”) playing had a huge impact on the New York Latin Jazz and rumba scenes. In 1995 Cuban pianist Alfredo Rodriguez (1936 – 2005), who was living in France at the time, returned to Cuba to record the album Cuba Linda. The track “Para Francia Flores” features La Conga de Los Hoyos with longtime members “Nene” Garbey on lead vocals (in the guaguancó section), Ramon “Monguito” Camacho on quinto and Valentin Serrano on corneta china. It is probably the first documented example of a full conga ensemble collaborating on a “fusion” recording, in this case conga mixed with afro-cuban jazz. It is also likely the first of many collaborations featuring Los Hoyos. Monguito played quinto in Los Hoyos from roughly 1980 to 2005. His playing style became a reference point and strong influence for future generations of quinto players, especially in Los Hoyos. This album also includes “Tumba mi Tumba,” a collaboration with Santiago's Tumba Francesa Society, one of only three remaining on the island. Jane y Los Hoyos Vienen Arrollando In 2001, Canadian sax/flute player Jane Bunnet released Alma De Santiago. This album features La Conga de Los Hoyos (including Monguito on quinto) on two tracks: “Jane y Los Hoyos” and “Donna Lee.” “Jane y Los Hoyos,” is an innovative arrangement of conga which includes the Santiago Jazz Saxophone Quartet. This is a successful “jazz-conga” fusion because it combines both genres to produce a natural-sounding result. “Donna Lee” is a mambo-jazz version of the Charlie Parker classic followed by a sudden segue into La Conga, w ith a few traditional coros (chants). “Alma De Santiago” also has a brief conga as a tag at the end. Conga-Pop; representing Oriente: Micaela “Añoranza por la Conga” (informally known as “La Conga de Micaela”) by Ricardo Leyva and Sur Caribe (2005) is a huge milestone for La Conga and Santiagueros. A catchy dance number with lead vocals, strings and of course, El Cocoyé (La Conga de Los Hoyos), “Añoranza” is unique in that it retains the flavor and irresistable drive of La Conga while “dressing it up” with a full band (strings, trombones, etc) for “mainstream” dancefloor consumption. The opening verses highlight the importance of conga to Santiaguer@s: Micaela se fue pa ́ otra tierra buscando caminos, que por buenos o malos quien sabe le impuso el destino. Solo vive llorando, sufriendo y pensando en su vino, que no es vino, señor; ni aguardiente, señor; es la conga, señor santiaguera. (from https://www.lyricsondemand.com/) My translation: Micaela left for another land,seeking new horizons For better or worse, it was her destiny She just goes on crying, suffering, and thinking about her wine But it’s not wine, sir, it’s not brandy... It is the conga, sir. From Santiago. The song was a big hit in Cuba and abroad; it won the Cubadisco 2006 Song of the Year award, and made it as far as Walmart. One observer deemed it #6 of Cuba's 20 biggest hits since 2000. I first heard it on a fairly mainstream playlist at a restaurant in Queens that I gigged at from 2016 to 2018. And of course it inspired at least one satire. In 2007, Sur Caribe released a conga version of “Hey Jude” as a homage to the Beatles, who had been deemed “counter-revolutionaary” and banned (along with rock and jazz in general) for many years in Cuba. The group’s next album, Horizonte Próximo, released in 2009, includes four more conga tracks. Electro-Conga, Auto-Tune and The YouTube Era Starting around 2010, younger artists began mixing conga with genres like rap and reggaeton. Most of these tracks replace or supplement the conga percussion ensemble with a computer/ sequencer generated beat. “Hasta Santiago a Pie (Conga 500 Aniversario)”, by Kola Loka, celebrates Santiago’s “Quincentennial” with shoutouts to the city's barrios, and a guest appearance by La Conga de San Agustin. Several Artists include footage of conga groups in their videos without any substantial conga element in their music. A few of these are in the playlist at the end of this post. I'll note here that the terms “urban” and “música urbana” have become controversial; I had been considering giving this section the title “Conga Urbana.” Invasion Jazzistica In 2014, another Cuban pianist named Alfredo Rodriguez (b. 1985) released “The Invasion Parade” a tribute to La Invasion, a long standing annual tradition where La Conga de Los Hoyos visits four of Santiago's rival Congas in a marathon street parade. After studying conga with Feliz Navarro of Cutumba in 2000, I became hooked and eventually recorded the title track of Quimbombó’s Conga Electrica, which came out in 2008. I mixed some Brazilian percussion concepts with my knowledge of conga at that time and got a result that I'm proud of. In 2016 Cuban Composer, pianist and flautist Oriente Lopez released “Arrollando el Carnaval” as part of his album Abracadabra. This track features multi-talented Angel Bonné (formerly with Los Van Van) on vocals and clarinet. “Arrollando” combines Oriente’s angular jazzy arrangement with a slamming groove that makes you want to take to the streets. Surpassing Havana? This post actually included many more tracks than I expected. Could it be that, in the 21st Century, Conga Santiaguera has a stronger presence on Cuban playlists and dancefloors than its rival from Havana? Is this a “boom” brought on by the success of “Añoranza por la Conga”? That's a rabbit hole for another day.... Discography Note: my recommended tracks are bold and underlined. Conjunto Corneta China. “Conga en Oriente /Goza Mi Conga.” Panart, 1950(?), 78 RPM. Ponce, Daniel “Siboney.” New York Now, Celluloid, 1983. Rodriguez, Alfredo (1936 – 2005). “Para Francia Flores.” Cuba Linda, Hannibal/Rykodisc, 1996. Percussion: La Conga de Los Hoyos Lead Vocals: “Nene” Garbey Bunnett, Jane. “Jane y Los Hoyos.” Alma de Santiago, Blue Note, 2001. Percussion: La Conga de Los Hoyos Bunnett, Jane. “Donna Lee.” Alma de Santiago, Blue Note, 2001. Percussion: La Conga de Los Hoyos Bunnett, Jane.“Alma de Santiago.” Alma de Santiago, Blue Note, 2001. Percussion: La Conga de Los Hoyos SurCaribe.“Añoranza por la Conga.”Credenciales, Egrem,2005. Percussion: La Conga de Los Hoyos El Gremio. “Conga Latina.” El Gremio, Bis Music, 2006. Sur Caribe. “Ay! Qué Felicidad.” Ay! Qué Felicidad, Egrem, 2007. Percussion: La Conga de Los Hoyos Sur Caribe. “Hey Jude.” Ay! Qué Felicidad, Egrem, 2007. Percussion: La Conga de Los Hoyos Quimbombó. “Conga Eléctrica.” Conga Eléctrica, Testa Dura, 2008. Percussion: Bloco La Conga (then known as Bloco Quimbombó) SurCaribe.“Arrollando por la Ciudad.” Horizonte Próximo, Egrem,2010. Percussion: La Conga de Los Hoyos Sur Caribe. "Bonito Bonito." Horizonte Próximo, Egrem, 2010. Percussion: La Conga de Los Hoyos Sur Caribe."Donde mi Cubana." Horizonte Próximo, Egrem, 2010. Percussion: La Conga de Los Hoyos Kola Loka. “Hasta Santiago a Pie (Conga 500 Aniversario).” La Alianza, Cubamusic Records, 2016. Chepin Reggae. “Conga Dans.” Mi Barrio, Yandris Araujo, 2013 Corneta China: Walfrido Valerino Cubanos en La Red. “La invasion.” Con Flow Guajiro, Caribe Sound, 2013 Percussion: La Conga de Los Hoyos Willetts, David. “Trueno De Chango.” Tem, David Willetts, 2013 Alejandro, Edesio. “Alalae.” 2013 Rodriguez, Alfredo (b. 1985). “The Invasion Parade.” The Invasion Parade, Mack Avenue, 2014. Percussion: Pedrito Martinez Drum Set: Henry Cole López, Oriente, “Arrollando El Carnaval.” Abacadabra, OHL Music, 2016. Lead Vocals: Angel Bonné Percussion: Mauricio Herrera Sources: Conga Fusion Youtube Playlist https://revista.drclas.harvard.edu/book/la-conga Correspondence with Lazaro Bandera, musical Director of La Conga de Los Hoyos Other Recommended Links: https://www.ritmacuba.com/chronologie-des-instruments-du-carnaval-Est%20de%20Cuba.html# 23 (in French) https://www.ritmacuba.com/textes-textos.html more about Sur Caribe: http://www.cubamusic.com/Store/Artist/1332 Alfredo Rodriguez (1936 – 2005): https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfredo_Rodr%C3%ADguez http://www.anapapaya.com/especial/e_arodrig.html An inspired essay on “Cuba Linda”

In December 2019, thanks to a reccomendation from Edgar Pantoja Aleman, I had the pleasure of taking a few singing lessons with Berta Armiñan Linares, an expert on traditional music from Oriente (Eastern Cuba). At one of our lessons she spoke about a little known style, the comparsita. What follows is my video, transcription and translation of a lesson/interview dealing with this style. My comments and clarifications are included in brackets in the transcriptions. BA: My name is Bertas Arminan Linares, founder of Conjunto Folklórico de Oriente, [Oriente Folkloric Ensemble] which was formed in May 1959.

I worked with this group until 1992, when I joined Cutumba, where i stayed until my retirement in 2009; I worked for 50 years in both groups. My role involved singing and dancing as well as teaching. The specific dances that I worked with were gagá, Tajona, and Tumba Francesa; I also sang these styles and some Yoruba songs. Today’s class deals with Comparsita, which emerged in the 20th century. Comparsitas used to form spontaneously during carnival [in Santiago]. Some friends would get together; and someone would bring a bokú [hand drum similar to a conga], someone else would have a bell, and everyone would start to sing and play. NH: Explain what a boku is. BA: ..nothing...boku is a drum, the one that plays the uno dos [“one two” pattern]. That is, for example: one of them [plays uno dos pattern on chair For example, in the song and rhythm we say for example (sings): “I’d like to be as tall as the moon Ay ay ay like the moon " That's the tempo of the Comparsita; ... and the bell simply does this [plays bell pattern and sings]: “I’d like to be as tall as the moon Ay ay ay like the moon to go up in the sky and be able to touch it ayayay to be able to touch it ” ...And so on… The songs would come up spontaneously, with a chorus following the lead singer. This would happen within families; for example, in my case, my family would have a verbena [street party]. Before carnival people would have street parties, and different families, friends, passers-by etc. would stop by to drink,eat, sing, have fun, etc. In my family, since there always were singers, musicians and dancers (in spirit of course), comparsitas would always get going around midnight.Because someone would get inspired-- my aunt Gladys for example, Gladys Linares, who played in La Conga de los Hoyos-- --they called her la campanera mayor "the chief bell player." I am the niece of Gladys de Linares "Mafifa." ..also my Aunt lydia, my Uncle Archimedes, my brothers and sisters...; I was little but they included me in that revolico [confusion, mess] to sing and play, and we would sing comparsita songs. For example: [sings] a “chin chin” It goes in a “chin chin” It goes out…” ...and so on until dawn. These are a few of the things that I can tell you about the comparsita. What happened was that, during carnival, friends and family would go to a Kiosk, to drink and eat; they’ fill the table with beer and soon enough, you'd have another conguita …[in this case another way of saying comparsita] They’d walk around and come back to the table to drink, and sometimes they’d carry a bucket of beer so they wouldn’t have to go back to the table. They’d take the bucket and stroll the avenues, singing, dancing and drinking. NH: So you were born in Los Hoyos [neighborhood]? BA: I was born at Escario and Sanmiguel, very close to the Moncada barracks. NH: Ok; and then you can can sing a few more examples of comparsita, with some improvisations? BA: Well, for example I have “rumbamba” here,which you already have, but let's do it again; help me out with the bell [pattern]; you have to do something!! NH If you want, you can do a few different chants: “La Luna , etc…” BA [SINGING]: Rumbambá rumbambá What a pretty girl! If her mother let her (??) I would marry her Such a pretty girl if her mother would let me Etc…. [Sirena Soy] Mermaid, I'm a mermaid Mermaid, I'm going to the sea “I’d like to be as tall as the moon Ay ay ay like the moon to go up in the sky and be able to touch it ayayay to be able to touch it ” Peasant, if you go to the country, Get up on the sidewalk [?] or I’ll knock you down. Peasant, if you go to El Caney [town near Santiago known for its delicious fruit] Bring me a mamey mango…. Guajiro if you hear the drum Get up on the sidewalk [?] or I’ll knock you down. [along with various untranslated improvisations] [La Jardinera] From the Cuban garden we will choose flowers And we’ll gather a bunch of evergreens (2x) We dedicate this to our audience I am a gardener... Flowers ! so many flowers! (2x) here comes La Jardiera [name of Havana comparsa group], Here it comes tossing flowers…. I hear a bass drum, baby it's calling me I hear a bass drum, baby it's calling me Oh God Oh God, it's Los Dandys! [name of Havana comparsa group], Oh God Oh God, it's Los Dandys! I hear a bass drum, baby it's calling me who? Who? The players! Get over there ! Hypocrite! [literally Pharisee] [fade out] BA [speaking]: Ha ha what a mess! NH: So, some of those chants [coros] were originally from comparsita others from conga, correct? ...or can any chant fit in? BA: Either can come up if it fits with the tempo... For example: [plays bell "uno y dos" of conga on chair] this beat inspires [certain chants], right? And then the beat of the comparsita [plays pattern] gives you the tempo. And so that helps the songs from the conga to fit into the comparsita, without any problem. The same goes for chants from paseo [style from Santiago close to conga Habanera] For example, I sang “La Jardinera,” which is from the paseo style, but it maintains the relationship [?to the clave]; it can be done, see? NH: Yes, it depends on the singer’s inspiration. B: Exactly, that's it! Why is Conga Santiaguera important?

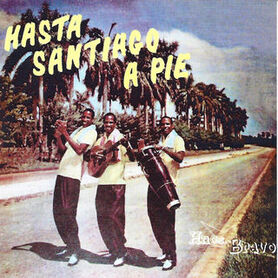

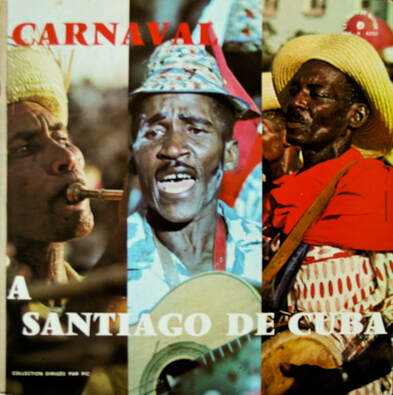

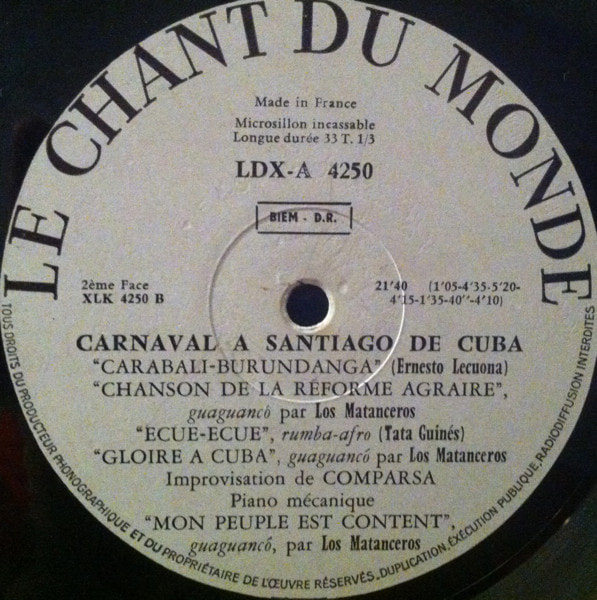

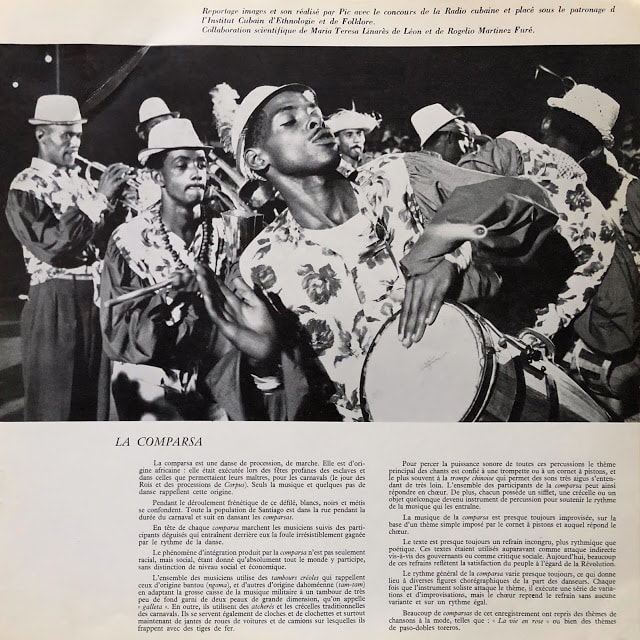

Because conga is essential to carnival in Santiago de Cuba --“sin conga no hay carnaval. Santiago has Cuba’s biggest and best carnival (Just ask any Santiaguero!); it is legendary throughout Cuba. And Cuba is the biggest island in the Caribbean; Santiago is a truly Caribbean city, while Havana faces the straits of Florida. Santiago’s carnaval is among the Caribbean’s, and the world’s, major festivals. Santiago is Cuba’s second most populous city, much smaller in population than Havana, but carnival is much more important to Santiagueros than it is to Habaneros, with a higher level of active participation. Since the 17th century, carnival in Santiago has consistently been in late July, centered around July 25, día De (day of) Santiago Apóstol, the patron saint of the city . Carnival in Havana currently occurs in the summer but the date varies; before the 1959 revolution it took place in February or March to coincide with the last days before Lent. It was also associated with January 6: El Dia de Reyes or Three Kings’ Day, when slaves and free people of color were permitted to parade with their African drums and songs. What is Conga? The word conga has at least three meanings (not counting the “conga drum” which is known as tumbadora in Cuba). It is a lively, drum-laden genre of Afro-Cuban music generally associated with carnival and street parades; regional variants include the conga Santiaguera, Camagüeyana, Habanera and Matancera. Conga also refers to the ensemble which plays this style: for example, in Santiago: La Conga de Los Hoyos, La Conga San Agustin, etc. Throughout Cuba these groups can also be referred to as comparsas depending on the performance context and region. In Santiago, a conga is also a sprawling, chaotic, mass of a few thousand people that surrounds the musicians in the streets. The expression “meterse en la conga” (literally “insert oneself in the conga”) means to become part of this mass, not necessarily to march amidst the musicians. The conga as an informal spontaneous street parade is an essential part of Santiago's culture. Conga for Santiagueros is much more than a rhythm or a band: it's an annual ritual, sweaty street party; it's rum, rebellion, Afro-Cubanidad, arrollando (a gyrating street dance), fights, and guapería (bravado). Conga Santiaguera is not as well known as the Conga Habanera (which is often called “comparsa” by musicians). The famous (?infamous?) “1,2,3 kick!” of the “conga line” comes from the Conga Habanera. Even Trio Matamoros' famous tribute, “Los Carnavales de Oriente" is done to a Conga Habanera rhythm. The Conga Habanera is more famous because Cuba's capital has always dominated its music and media industries, and therefore shaped perceptions of Cuban music and culture outside the island. Havana's Conga, like other Afro-Cuban styles from Western Cuba, is more familiar to musicians outside the island; it has been studied, taught and transcribed more. We at laconga.us hope to change that: our primary mission is to spread the word about the conga santiaguera. I'll close with a couple of quotes: From https://www.ecured.cu: "La conga en Santiago de Cuba (Conga Santiaguera), es para los cubanos un acontecimiento trascendental con un significado muy bien definido. Cuando se menciona la palabra “Conga”, es como si se hubiera dicho ¡A Gozar!" The conga santiaguera is, for Cubans, a transcendental event with a well defined meaning. The word ”conga” is synonymous with “party!!!” From http://www.cultstgo.cult.cu: "Cuando se ha hablado del Carnaval refiriéndose a Cuba se ha pensado siempre, primera y principalmente en los de Santiago de Cuba." When people talk about Carnival in Cuba, they always remember, first and foremost, Santiago de Cuba. Before YouTube, commercial audio recordings were primary source of information for musicians, much more so than today. This post will look at commercially released recordings (vinyl and CD) of conga santiaguera; some of these are labled as "conga oriental" so I'll attempt explain these two terms. Oriental or Santiaguera? The term Oriente refers to the Eastern region of Cuba; it was a province until 1976 when it was split up into Las Tunas, Granma, Holguín, Santiago de Cuba, and Guantánamo Provinces. My limited research indicates that the conga rhythm as it is currently played in Oriente is mainly derived from the Santiaguera style with its characteristic tambora (bass drum) accent right before the downbeat. Of course, different cities in the region have their own styles and variants; for example, Guantanamo's congas seem to use four bells (instead of three as in Santiago) and sometimes have a brass section instead of a corneta china. The terms I prefer are: santiaguera if its from Santiago or mostly based on that style; oriental to refer to a style from Oriente outside of Santiago. 1. Conjunto Corneta China: Conga en Oriente /Goza Mi Conga This recording was originally issued as a 78 by Panart, probably in 1950 if we assume their catalog numbers are consistently in chronological order. It was also reissued as a 45, probably some time in the late 1950s. Ironically it is in a non-traditional “band” format with a piano and bass in addition to percussion, vocals, and the trademark corneta china. The percussion instruments are probably not all from a traditional conga: they sound like cowbell, conga drums and one or more bass drums. It is very likely that the corneta player and some of the percussionists are from La Conga de Los Hoyos, who, according to an informant cited here, visited Havana in 1950 and rehearsed a few blocks away from the Panart studio. It seems odd to me that percussionists from Los Hoyos would not use to their own traditional instruments to record, but its difficult to verify if the musicians at this session were indeed from Los Hoyos. According to an article by Rolando Antonio Pérez Fernández , there was a group known as "La Corneta China" that performed at a Santiago carnival dance in 1941, but it is very unlikely that this same group traveled to Havana or recorded at all. A web search for "Conjunto Corneta China" invariably leads to the Panart recording. It is much more likely that this recording was made by a "pick up" group of Havana session musicians, and probably the corneta player and some percussionists from Los Hoyos. In addition there is little if any evidence that the corneta china was used by comparsas in Havana at this time. The pianist, who solos on both tracks, sounds familiar to me and is probably someone that appears on other Panart recordings: maybe Julio Gutierrez or Perchuin. Despite the absence of some of the traditional percussion instruments, the over all rhythmic feel of the recording is authentic enough to consider it a “true” conga Santiaguera. Side A: “Conga en Oriente” The track starts with a typical rubato corneta call and drum/percussion roll. After a few measures of corneta soloing over percussion, bass and piano, the first coro (chant or refrain) begins : Si tú eres consciente Y te gusta guarachar Ven acá para nuestro oriente A gozar en el carnaval If you're conscious And you like to party Come see us in Oriente [Eastern Cuba] And enjoy the carnaval (The message here is: "If you dont like Carnival in oriente, you must be unconscious!") Normally in a conga performance, the corneta china plays the coro melody first and then the musicians and crowd respond by singing the coro; this does not occur on either of these tracks. The coro enters without being “called” by the corneta; the corneta then improvises in between coros. After a short piano solo comes the second coro: Me voy a oriente A gozar en el carnaval Im going to oriente To enjoy the carnival. Side B: "Goza mi conga" This track also starts with a rubato section and a short corneta improvisation, followed by the first coro: Mamá que fue (se fue?) (2x) A los carnavales de oriente me voy (2x) Mom [she] went Im going to carnival in oriente [too] This Coro is the only one on either of these tracks that I've heard in other settings; it's one of many in the traditional Conga Santiaguera repertoire. After a short piano solo, (with the some quinto variations that definitely sound Santiaguero to me) the last Coro comes in: Goza mi conga como es Enjoy my Conga as it is 2. Los Hermanos Bravo: "Hasta Santiago a Pie" Originally released in 1960 on RCA VICTOR, according to Fidel’s Eyeglasses, an excellent blog, this track is listed as a “Poupurrit de Congas Orientales” and seems to have been quite popular in Cuba in the early 1960s. The first part of the track is done to a Conga Habanera rhythm; at 1:05 the groove changes for the coro “Hasta Santiago a pie.” The percussion style here is closer to “comparsita” than conga santiaguera. Comparsita is a style that I became aware of at a 2019 lesson/interview with Bertha Armiñán Linares in Santiago. “Hasta Santiago a pie” ([Let’s go] to Santiago by foot) is a very common coro in Santiago. Here are the other coros: Agua, que va a llover Water ! Its gonna rain This melody/chant is fairly common in both rumba (i have heard it in New York park rumbas), salsa and (in a modified form) conga santiaguera. Mori bo ya ya (a Yoruba religous chant) Veinte le doy a mi gallo pelon (roughly!) Ill bet twenty on my bald rooster These last two coros probably have their origins in Havana or Matanzas. 3. Carnaval À Santiago De Cuba -- Le Chant Du Monde LP This LP was probably released in 1967 (I have seen various dates between 1959 and 1967 cited) and has not been reissued on CD or digitally. It includes what i would call "field recordings" of conga santiaguera, most likely recorded in the streets of Santiago in 1960 or 1961. Of the three releases discussed in this post, this is by far the most authentic. The album includes four tracks of conga; no perfomer credits other than “comparsa musicians” are given. These tracks could be the earliest fully authentic recordings of conga santiaguera. More on this album in these blogs: Fidel's Eyeglasses, Music Republic, and MuzzicalTrips. The tracks: Ambiance De Rue Because of the syncopated bell playing (similar to patterns used in the Conga Habanera rhythm), this track is probably La Conga San Agustin. During my recent trips to Santiago, I learned that San Agustin is the only conga where the “uno y dos” (usually medium pitched) bell improvises. The “uno y dos” and “un solo golpe” bells have a “conversation” where both bells improvise simultaneously; I was unable to actually record San Agustin's bell players playing in this style but I'm including here a brief interpretation by two musicians from La Conga de Los Hoyos. Many of the younger Conga musicians in Santiago showed a great respect for and interest in, the styles of their rival Congas. This is very similar to the musical camaraderie, interest and respect that I've seen between batuqueiros (drummers) from Rio de Janeiro's various samba schools. El Macuquillo Oriental Because the requinto is the drum that opens the conga groove (around :07 here), I will guess that this is La Conga de Los Hoyos. Lazaro Bandera, current musical director of Los Hoyos and a very knowledgeable historian of this genre, explained to me that, in Los Hoyos for many years the requinto was the drum that would start the conga groove. The rhythm in this track this also switches to Columbia and then back to Conga (Pilón), which could indicate that it's Los Hoyos. The traditional practice of Los Hoyos, however, has been to play Pilón, Columbia and Masón as a complete cycle. Improvisation de Comparsa (from Side A) This track is very useful for musicians; it has some well recorded quinto and tambora (a.k.a galleta or redoblante) improvisations. My teacher Lazaro Bandera Malet identified this track as likely being from Conga San Pedrito. He cited the tempo (relatively fast), the inclusion of a guayo (metal scraper) and the styles of corneta and tambora playing as evidence. Improvisation de Comparsa (from Side B) The ensemble here includes claves and maracas (or similar shakers), which are not traditional conga instruments. There are a few well recorded tambora and un solo golpe bell variations toward the end. Because of the slightly slower tempo, this is probably Conga Paso Franco. This album also contains a rare recording of a Comparsa Carabali from Santiago; the track, "Carabali - Burundanga;" includes a corneta china, which is quite unusual for this style. The release also has tracks by the great Tata Guines and Grupo Guaguancó Matancero (who would later become famous as "Los Muñequitos De Matanzas". ConclusionsThe Panart record is important because, despite using a non-traditional ensemble format, it may be the first recording of Conga Santiaguera. The Hermanos Bravo track is included here because it refers to Santiago and Oriente, has some some musical elements of these places, and was fairly well known in Cuba when it came out. The Chant Du Monde release is very important as possibly the first recording of conga made in the streets of Santiago, where this genre was born. It is also an excellent resource for percussionists.

**NOTE: Due to some formatting problems I have placed all notes at the end of this post. |

|||||||||||||||||

| pilon_col_mason.pdf | |

| File Size: | 1206 kb |

| File Type: | |

Conga Santiaguera, the signature rhythm or “groove” of Santiago de Cuba’s street carnival, is a musical phenomenon that has not been transcribed or researched sufficiently.

Relatively few people outside of oriente (Eastern Cuba) play this rhythm, and even fewer know about the full three part cycle described below. This is in stark contrast to styles from Western Cuba such as conga Habanera (a.k.a. “Comparsa”) rumba, palo, and batá drumming, which are (relatively) widely studied and performed throughout Cuba and the world.

THE INSTRUMENTS:

Conga ensembles consist of voices, percussion and a corneta china, a loud double reed instrument that plays melodies and improvises.

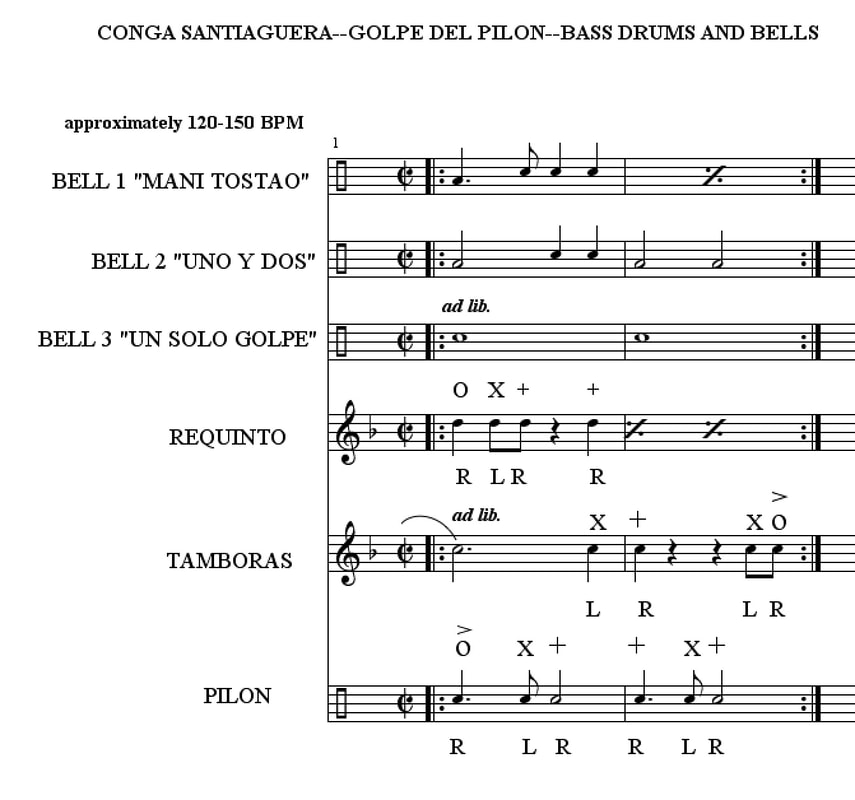

BASS DRUMS (all played with a heavy stick on the top head and a bare hand on the bottom head):

Pilón: A large, two headed bass drum.

Tamboras :(a.k.a. galletas, redoblantes or congas) are sliightly smaller than the Pilon, but similar in shape. Normally a conga ensemble uses two tamboras, which take turns improvising. (Note: These are not the same as a Dominican tamboras!)

Requinto: A fairly small bass drum, similar in size to a large tom tom from a drum set.

BELLS:

Typically, three brake drums from old cars are struck with metal sticks. The names of the three “campanas” (bells) are:

“Maní tostao” (I also refer to this as Bell #1): smallest and highest pitched.

“Uno y dos” or “Tres-dos” (Bell #2): second smallest and second highest pitched.

“Un Solo Golpe” or “Can” (Bell #3): largest and lowest pitched; this is the only bell that improvises in the pilon rhythm and changes its patterns for the Columbia and Mason.

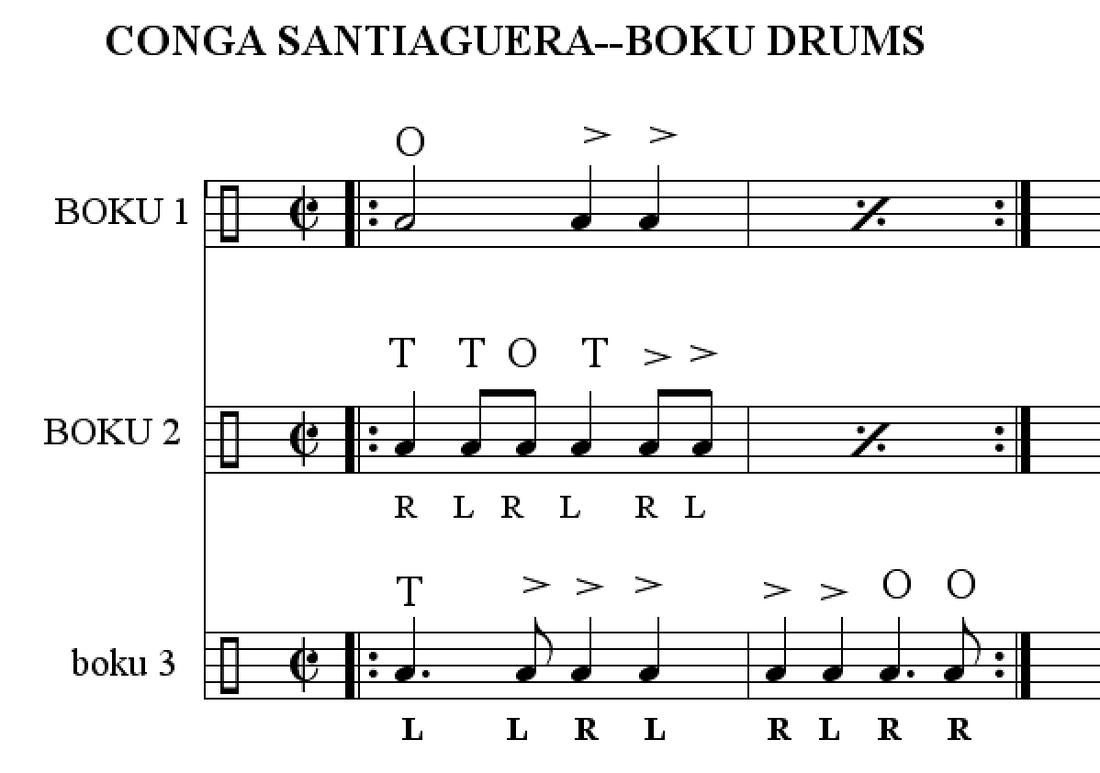

HAND DRUMS: BOKUS OR FONDOS:

The boku or fondo is a conical drum very similar to a “conga drum” or tumbadora. The technique for boku is basically the same as for conga drums. The highest pitched boku, the quinto, is usually the first drum to start playing (after the corneta china plays its opening “call”). Conga ensembles often include 15 or more of these drums; the transcriptions included here are examples of a few of the more common patterns. After the ensemble enters, the quinto usually improvises throughout the performance.

Pictures of these instruments can be found here:

The Three Rhythms or “Movements”:

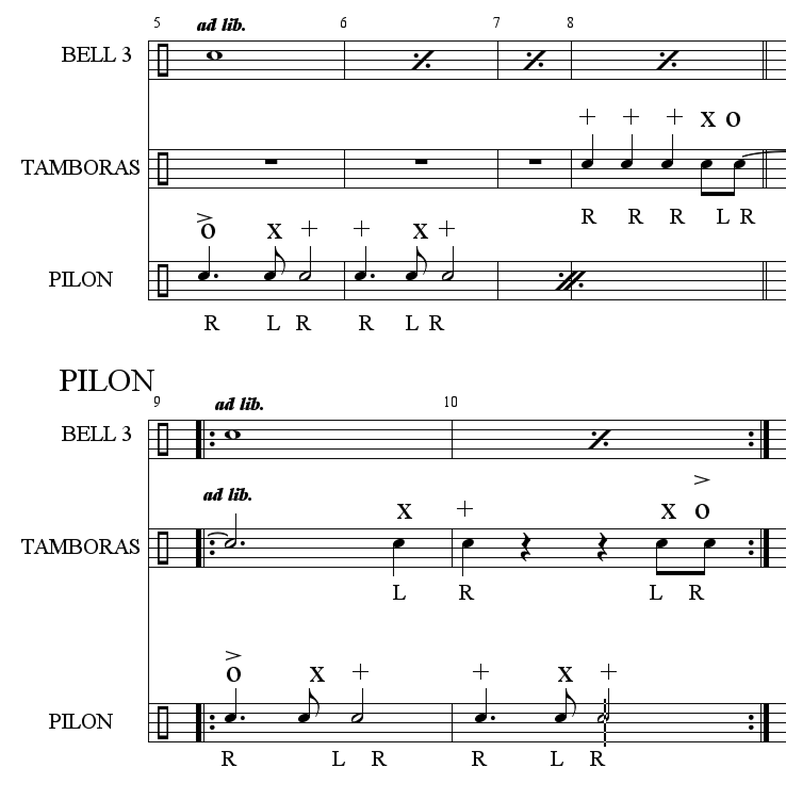

Pilon[1] or Quirina

The Golpe del Pilón (aka Golpe Quirina) is the predominant, essential, and best known “groove” of the conga. All performances and recordings that can be considered conga santiaguera or conga oriental (“Eastern Conga”) include this groove.

Many musicians in Santiago refer to the Pilón rhythm as “conga.”

A more detailed description and transcription of the Pilón can be found in this blog post. In the Pilón rhythm, the quinto and the un solo golpe bell improvise; the two tamboras take turns improvising (ad lib is indicated in the transcription)

I'm including a transcription [2] for right handed players here, using the following notation:

BASS DRUMS:

O = OPEN STROKE WITH STICK

+= CLOSED STROKE WITH STICK (LEFT HAND MUFFLING BOTTOM HEAD)

X = SLAP WITH LEFT HAND ON BOTTOM HEAD

BELLS:

Different pitches on staff approximate higher and lower pitched sounds on brake drum. Lower pitched sounds are slightly accented.

BOKUS:

O = TONE

> = SLAP

T= TIP (FINGERTIPS)

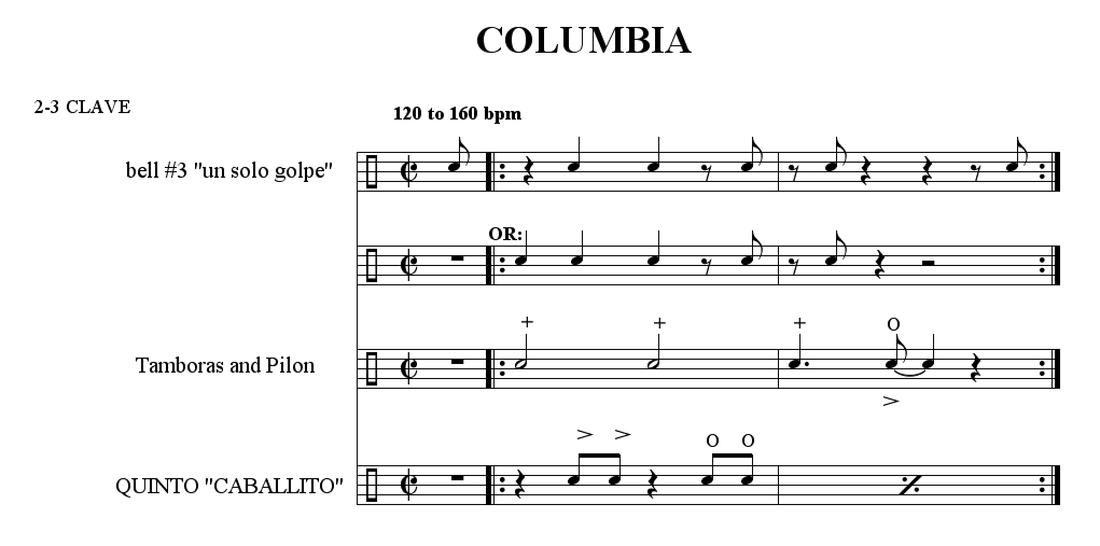

COLUMBIA

When listening to recordings of Conga, one occasionally hears the bass drums (pilon and two tamboras) briefly shift to a new groove. For example, if you listen to this recording, at 2:17 the bass drums seem to shift to a conga habanera pattern. In the context of the Conga, this is known as “El Golpe de La Columbia” or simply “Columbia” [3]. At 2:37, The bass drums switch to a new pattern known as “Masòn” before returning at 2:48 to “El Golpe del Pilón” or Pilón.

In Columbia and Masón, the only instruments whose patterns consistently differ from the Pilón rhythm are the “un solo golpe” bell, the Pilón, and the two Tamboras. The “un solo golpe” bell player has two different patterns to choose from; generally this player maintains the same pattern throughout the Columbia.

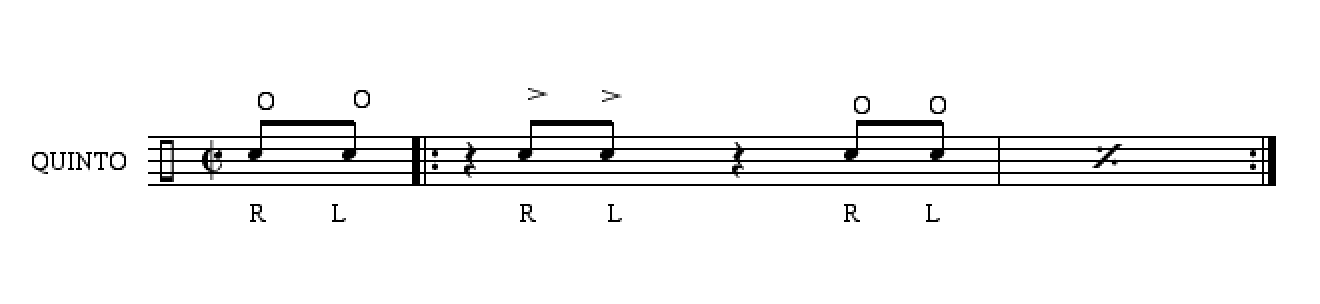

The Quinto usually plays the “caballito” pattern (shown here) during the Columbia; sometimes it continues to improvise.

The requinto, most of the bokuses, and the “mani tostao” and “uno y dos” bells maintain the same pattern for Pilon, Columbia and Masón.

This pattern as notated implies a 2-3 clave .

Note that the first bell pattern shown begins just before the downbeat and then repeats a two measure cycle. This will be described further in the section on transitions.

When listening to recordings of Conga, one occasionally hears the bass drums (pilon and two tamboras) briefly shift to a new groove. For example, if you listen to this recording, at 2:17 the bass drums seem to shift to a conga habanera pattern. In the context of the Conga, this is known as “El Golpe de La Columbia” or simply “Columbia” [3]. At 2:37, The bass drums switch to a new pattern known as “Masòn” before returning at 2:48 to “El Golpe del Pilón” or Pilón.

In Columbia and Masón, the only instruments whose patterns consistently differ from the Pilón rhythm are the “un solo golpe” bell, the Pilón, and the two Tamboras. The “un solo golpe” bell player has two different patterns to choose from; generally this player maintains the same pattern throughout the Columbia.

The Quinto usually plays the “caballito” pattern (shown here) during the Columbia; sometimes it continues to improvise.

The requinto, most of the bokuses, and the “mani tostao” and “uno y dos” bells maintain the same pattern for Pilon, Columbia and Masón.

This pattern as notated implies a 2-3 clave .

Note that the first bell pattern shown begins just before the downbeat and then repeats a two measure cycle. This will be described further in the section on transitions.

MASÓN

The masón rhythm of the conga is related to the masón of the tumba francesa; this will be discussed in the section on origins.

During a performance of the Pilón-Columbia-Masón “cycle,” the masón rhythm is played immediately after the Columbia. As in the Columbia, only the

“un solo golpe” bell, the Pilón and the two Tamboras change their patterns. The Pilón and tambora pattern is adapted directly from the masón of the tumba francesa, which uses a small tambora or “tamborita.”

The masón rhythm of the conga is related to the masón of the tumba francesa; this will be discussed in the section on origins.

During a performance of the Pilón-Columbia-Masón “cycle,” the masón rhythm is played immediately after the Columbia. As in the Columbia, only the

“un solo golpe” bell, the Pilón and the two Tamboras change their patterns. The Pilón and tambora pattern is adapted directly from the masón of the tumba francesa, which uses a small tambora or “tamborita.”

Recently, La Conga de Los Hoyos and Conga Paso Franco [4] have changed their quinto patterns for the Mason rhythm, but this practice is not nearly as standardized as the use of the caballito pattern for the Columbia. The quinto pattern they play is based on the “quijá” pattern from the tajona, a genre closely related to the tumba Francesa. Shown here is one of a few versions of this pattern that i observed:

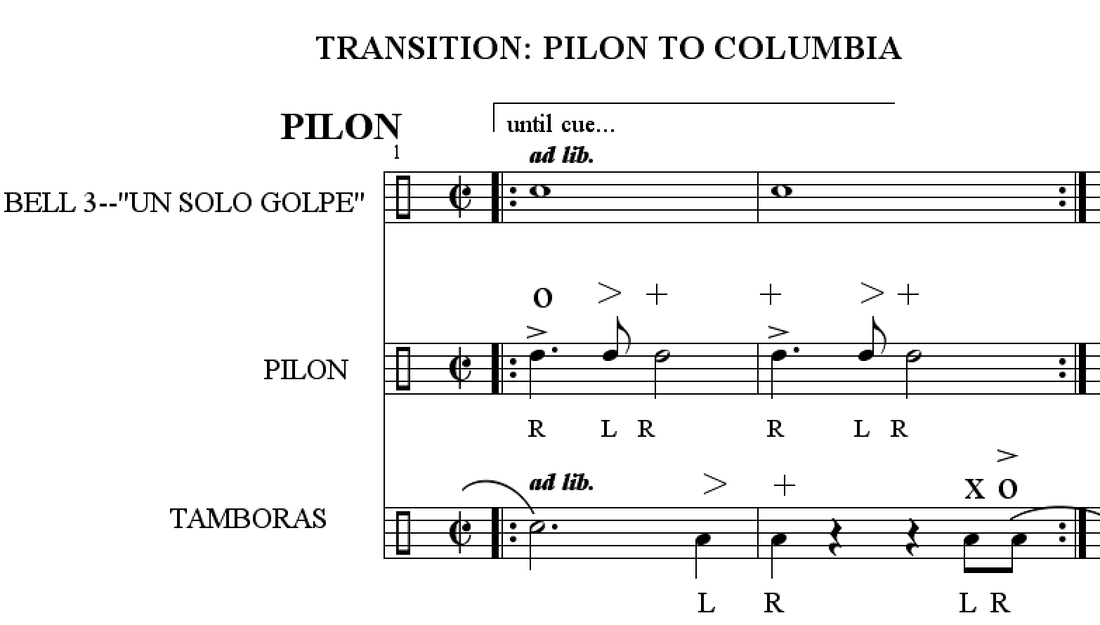

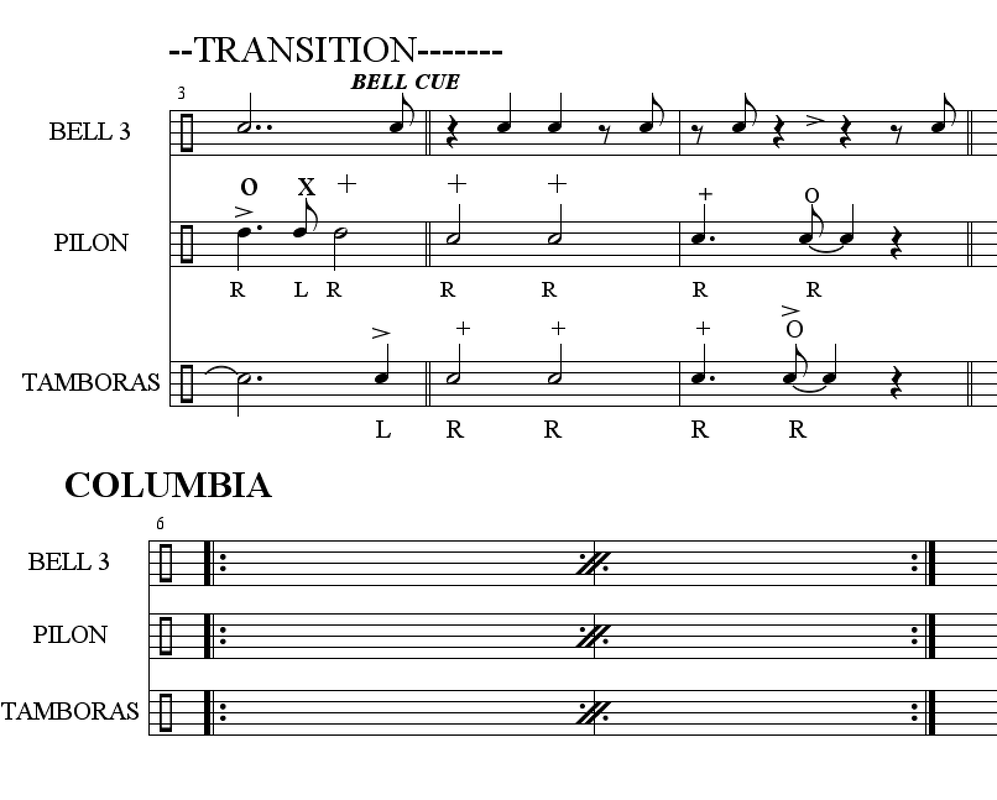

Transition: Pilon to Columbia

This transition is signaled by the “un solo golpe” bell player.

The Pilon, Tambora and quinto players must be alert and ready to respond to this call.

This transition is signaled by the “un solo golpe” bell player.

The Pilon, Tambora and quinto players must be alert and ready to respond to this call.

For the quinto, the transition to caballito occurs on beat 4:

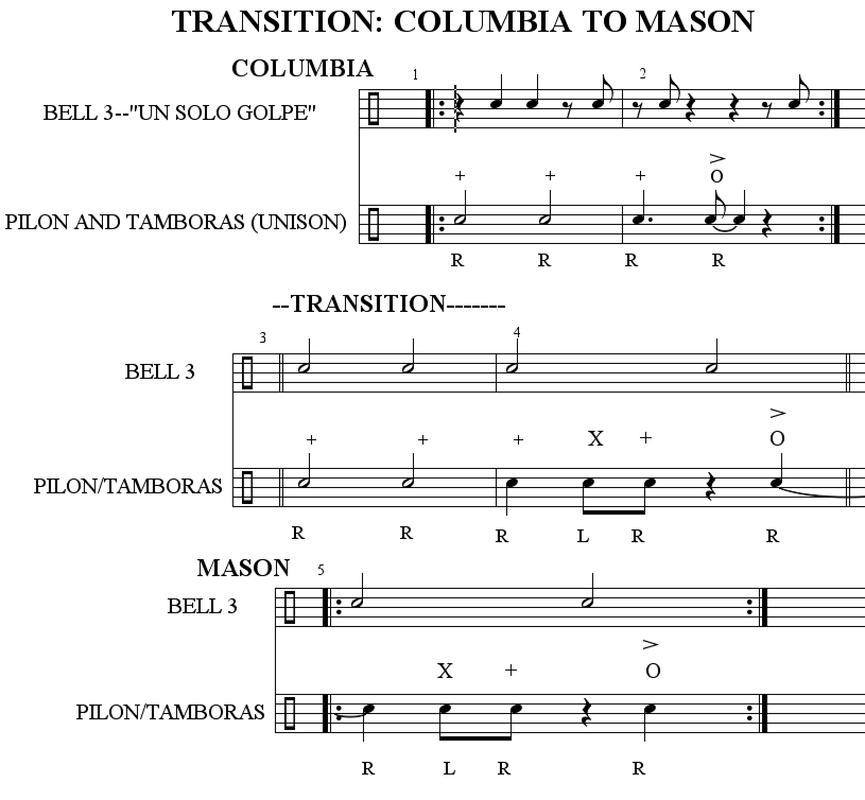

Transition : Columbia to Masón

The transition from Columbia to Mason is signaled by the “un solo golpe” bell player. This player will switch from the syncopated columbia pattern to the much more “straight” Mason pattern:

The transition from Columbia to Mason is signaled by the “un solo golpe” bell player. This player will switch from the syncopated columbia pattern to the much more “straight” Mason pattern:

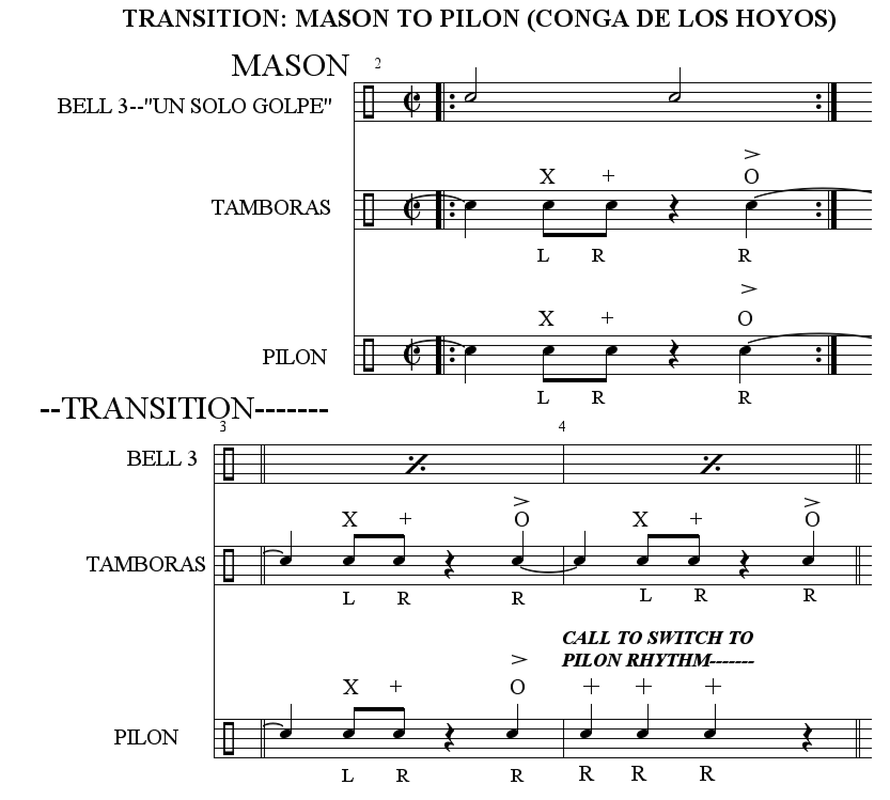

Transition : Mason to pilon

Of the three transitions, the change from Mason back to Pilon seems to be least standardized and consistent. In my studies I've seen a few different versions of this transition. Because La Conga de Los Hoyos is the Conga whose music I'm most familiar with, I will start with their current transition, as explained to me by musical director Lazaro Bandera Malet during private classes in June 2019.

According to Lazaro the Pilon drum calls the transition back to the Pilon rhythm by playing the following phrase on the “two side” of the clave:

Of the three transitions, the change from Mason back to Pilon seems to be least standardized and consistent. In my studies I've seen a few different versions of this transition. Because La Conga de Los Hoyos is the Conga whose music I'm most familiar with, I will start with their current transition, as explained to me by musical director Lazaro Bandera Malet during private classes in June 2019.

According to Lazaro the Pilon drum calls the transition back to the Pilon rhythm by playing the following phrase on the “two side” of the clave:

The tamboras sometimes respond a few measures later with the following phrase (also on the “two side” of the clave) to signal their transition back to the Pilon rhythm:

The entire transition would look like this:

In Conga Paso Franco, the quinto signals the transition from Masón to Pilón.

This “call” is essentially the same phrase that the quinto plays at the beginning of a performance after the corneta china plays its call:

This “call” is essentially the same phrase that the quinto plays at the beginning of a performance after the corneta china plays its call:

I'll note here that the Masón to Pilón transitions transcribed here are based on my lessons with Lazaro and Kiki. I've observed slightly different transitions when watching these two congas rehearse.

Origins and performance practice -- Pilon

The Pilon rhythm is generally agreed to have originated in La Conga de Los Hoyos, Santiago's oldest [5] and most famous and influential conga. Mililián Galis Riveri “Galí” [6] cites the influence of gagá (rara), a genre from Haiti, in the creation of this rhythm when it debuted in 1914. I would agree that the overall feel of Pilon is very similar to that of rara, but I am not aware of any research directly linking the two [7].

The conga santiaguera’s characteristic syncopated tambora accent (just before the downbeat) is believed to have been created by “Nanano”, a musician from Los Hoyos, in the 1930s. A few years later “Pililí” (also from Los Hoyos) began to improvise on the tambora.

Origins and performance practice --Columbia

The Columbia definitely resembles the Conga Habanera (a.k.a “comparsa” rhythm) due to its strong bass drum accent on the “and” of beat two on the “three-side” of the clave.

Gali attributes the Columbia to the influence of the conga rhythm as played in Havana and Matanzas in the early 1900s. According to Gali, ex-soldiers from Matanzas taught other musicians in the Tívoli neighborhood of Santiago to play Columbia (based on conga Habanera or Matancera style In 1913. La Conga del Tivoli debuted in that year’s carnival playing this rhythm [8].

The name “Columbia “ has at least two possible sources: a military camp in Havana, where some Santiagueros were stationed, or a railroad station in the province of Matanzas. This rhythm is not directly related to the rumba columbia. In my class with Bandera, he stated that the “un solo golpe” bell pattern for Columbia originated in La Conga de Los Hoyos and is derived from the 12/8 bell pattern used in rumba columbia.

Many informants have also stated that the Columbia is played while climbing hills during parades. Columbia and mason are also performed while the conga is stationary; Los Hoyos traditionally plays Columbia and Masón near the end of a parade when they are close to their foco cultural (headquarters).

Origins and performance practice -- Masón

According to Galí, the first use of the Golpe del mason in the Conga is generally believed to have been in 1936 [9]. Gali stated to me that “Nanano,” tambora player of Los Hoyos was the first to adapt this pattern to the conga context.

The mason pattern as played on the Pilon and Tamboras in the conga is the the only consistent musical link to the tumba francesa; as stated above, Bandera has recently started to change the quinto (and some boku) patterns in Los Hoyos to more definitivelty “declare” a mason rhythm [10].

Conclusions

There is little dispute that the Pilon and Mason rhythms originated in La Conga de Los Hoyos and that the Columbia rhythm originated in La Conga del Tívolí.

At this point it is not clear whether all eight congas in Santiago consistently include the Pilón -Columbia -Mason cycle in their perfomances. In my 2019 visit to santiago I saw Los Hoyos and Paso Franco play the full three part cycle. I saw el Guayabito and San Agustin play the Columbia but not the Mason.

It seems that the tradition of playing this cycle originated with, and continues to be strongest in, La Conga de Los Hoyos . From my brief observation, Los Hoyos seemed to have the most consistent and organized transition. I also confirmed with Bandera that Los Hoyos always plays columbia and mason when they parade. It's hard to say whether the other Congas consistently play this cycle.

I'd argue that the Columbia and Mason rhythms are performed mainly as a way of maintaining tradition. The Pilon rhythm is played for the vast majority of any parade or performance. When listening to recordings, the Columbia is easier to recognize than the Masón because of its strong bass drum accent. Columbia and Mason are usually played for around a minute (or less) each, making it sometimes difficult to dístinguish hem.

NOTES:

[1] Not to be confused with the Pilón dance rhythm popularized by Pancho Alonso in the 1960s. There is, however, a little known connection between between the “Pilón” of the conga and the “Pilón” of popular music: the drummer Esmerido "Loló" Ferrera. For more info see: https://www.ritmacuba.com/pilon.html (in French).

[2] The patterns shown here are the most common ones used by the various Congas in Santiago. There are, of course, variants; for example, the Conga de Los Hoyos has its own slightly different patterns for the requinto drum and the “uno y dos” bell. My main sources for the patterns transcribed are Lazaro Bandera, musical director of Los Hoyos, and Richard Leonel “Kiki” Ferrera, musical director of Conga Paso Franco. Also note that the un solo golpe and tambora patterns shown here are points of departure for improvisation.

Also, as with most music from the African diaspora, transcriptions cannot adequately represent the sound and feel of the style. Repeated listening, study, and observation is necessary to play this music.

[3] Not to be confused with Rumba Columbia which is generally believed to be from Matanzas province.

[4] Based on 2019 interviews with musical directors of these two Congas.

[5] While many point to La Conga del Tivoli as the “first” conga in Santiago, most santiagueros refer to La Conga de Los Hoyos as the oldest and “most traditional” conga and cite a founding date of 1902. Part of this dispute, in my opinion, depends on how we define “conga.” There is little doubt in my mind that Los Hoyos is the oldest continuously existing conga. La Conga del Tívoli disbanded in 1939. More on this in another post...

[6] Gali’s book “La percusión en los ritmos afrocubanos

y haitiano-cubanos" is, to my knowledge, the most in-depth source of written information about the music, history and origins of the conga santiaguera; it is the main source for my discussion of the origins of Pilon, Columbia and masón.

[7] It is also hard to say whether gagá was actually performed in Cuba in 1914. More research is needed.

[8] See footnote 6

[9] https://www.cndenglish.com/index.php/en/noticia/conga-los-hoyos-pride-santiago

Claims an origin date of 1938.

[10] Lesson/interview with Lazaro Bandera, June 2019

Acknowledgements and Sources

Thanks to:

Felix Bandera, director of La Conga de Los Hoyos, and Lazaro Bandera Malet, musical director, for generously sharing their extensive knowledge of this tradition.

Richard Leonel “Kiki” Ferrera, musical director, and all the members of Conga Paso Franco for sharing their knowledge.

Raul Lopez Martinez, director of Conga San Agustín, for his warm welcome and detailed explanations of his Conga’s style.

Daniel Chatelain of http:www.ritmacuba.com/ for sharing incredible amounts of information, both on his website and via email.

Galis Riveri, Mililián “Galí,” for clearing up a few doubts I had about material in his incredible book.

Lani Milstein for sharing information via email. Her excellent and very detailed thesis includes her own transcriptions of Pilon, Mason and Columbia.

Lani also wrote this excellent article which helped inspire me to quit procrastinating and go to Santiago!

The transcriptions included here are based on my own private lessons with Lazaro Bandera and other teachers in Santiago, and repeated viewings of this video.

Recordings and videos

"El Toque de Los Hoyos": an excellent demonstration of Pilón, Columbia and Masón by Lazaro Banderas and musicians from Los Hoyos.

A few relevant playlists:

CONGA SANTIAGUERA--GOOD RECORDINGS

CONGA SANTIAGUERA- “CYCLE”--PILON, COLUMBIA, AND MASÓN

Documentary: "Se Llama Conga"

Other links:

Lani Milsteins article

Article about Conga de Los Hoyos

https://www.bluethroatproductions.com/video/conga-series

Ritmacuba article (in french) about the instruments of the conga. Ritmacuba.com is a great resource.

BOOKS:

Mililián Galis Riveri “Galí”.

La percusión en los ritmos afrocubanos y haitiano-cubanos. Santiago de Cuba: Ediciones Caserón, 2015. Print;

includes transcriptions and history of conga santiaguera dating back to 1913.

Millet, José, Rafael Brea, and Manuel Ruiz Vila.

Barrio, Comparsa y Carnaval Santiaguero. Santo Domingo: Ediciones Casa del Caribe, 1997. Print.

An in depth study of the Los Hoyos neighborhood in Santiago and its conga. Interviews with key members of La Conga de Los Hoyos and evidence of the importance of carnival and conga to the culture and history of Santiago.

Author

Nick Herman is a New York-based percussionist, educator, composer and arranger.

Archives

May 2023

July 2020

May 2020

March 2020

December 2019

RSS Feed

RSS Feed