**NOTE: Due to some formatting problems I have placed all notes at the end of this post. |

|||||||

| pilon_col_mason.pdf | |

| File Size: | 1206 kb |

| File Type: | |

Conga Santiaguera, the signature rhythm or “groove” of Santiago de Cuba’s street carnival, is a musical phenomenon that has not been transcribed or researched sufficiently.

Relatively few people outside of oriente (Eastern Cuba) play this rhythm, and even fewer know about the full three part cycle described below. This is in stark contrast to styles from Western Cuba such as conga Habanera (a.k.a. “Comparsa”) rumba, palo, and batá drumming, which are (relatively) widely studied and performed throughout Cuba and the world.

THE INSTRUMENTS:

Conga ensembles consist of voices, percussion and a corneta china, a loud double reed instrument that plays melodies and improvises.

BASS DRUMS (all played with a heavy stick on the top head and a bare hand on the bottom head):

Pilón: A large, two headed bass drum.

Tamboras :(a.k.a. galletas, redoblantes or congas) are sliightly smaller than the Pilon, but similar in shape. Normally a conga ensemble uses two tamboras, which take turns improvising. (Note: These are not the same as a Dominican tamboras!)

Requinto: A fairly small bass drum, similar in size to a large tom tom from a drum set.

BELLS:

Typically, three brake drums from old cars are struck with metal sticks. The names of the three “campanas” (bells) are:

“Maní tostao” (I also refer to this as Bell #1): smallest and highest pitched.

“Uno y dos” or “Tres-dos” (Bell #2): second smallest and second highest pitched.

“Un Solo Golpe” or “Can” (Bell #3): largest and lowest pitched; this is the only bell that improvises in the pilon rhythm and changes its patterns for the Columbia and Mason.

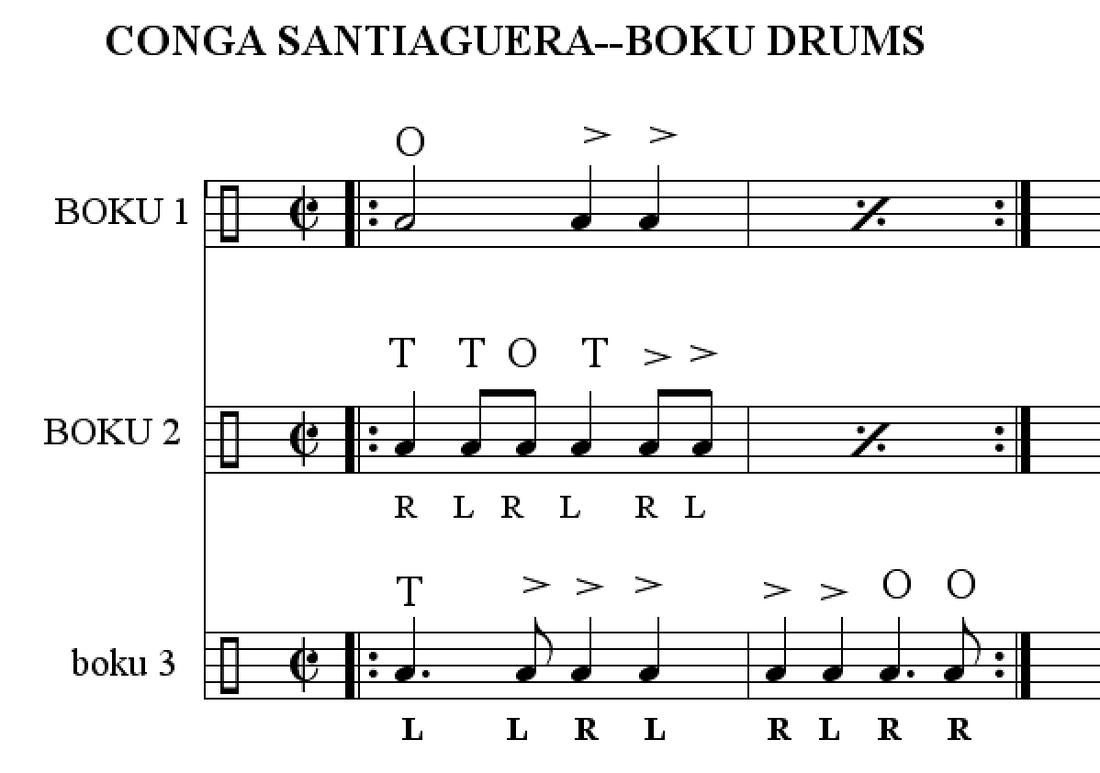

HAND DRUMS: BOKUS OR FONDOS:

The boku or fondo is a conical drum very similar to a “conga drum” or tumbadora. The technique for boku is basically the same as for conga drums. The highest pitched boku, the quinto, is usually the first drum to start playing (after the corneta china plays its opening “call”). Conga ensembles often include 15 or more of these drums; the transcriptions included here are examples of a few of the more common patterns. After the ensemble enters, the quinto usually improvises throughout the performance.

Pictures of these instruments can be found here:

The Three Rhythms or “Movements”:

Pilon[1] or Quirina

The Golpe del Pilón (aka Golpe Quirina) is the predominant, essential, and best known “groove” of the conga. All performances and recordings that can be considered conga santiaguera or conga oriental (“Eastern Conga”) include this groove.

Many musicians in Santiago refer to the Pilón rhythm as “conga.”

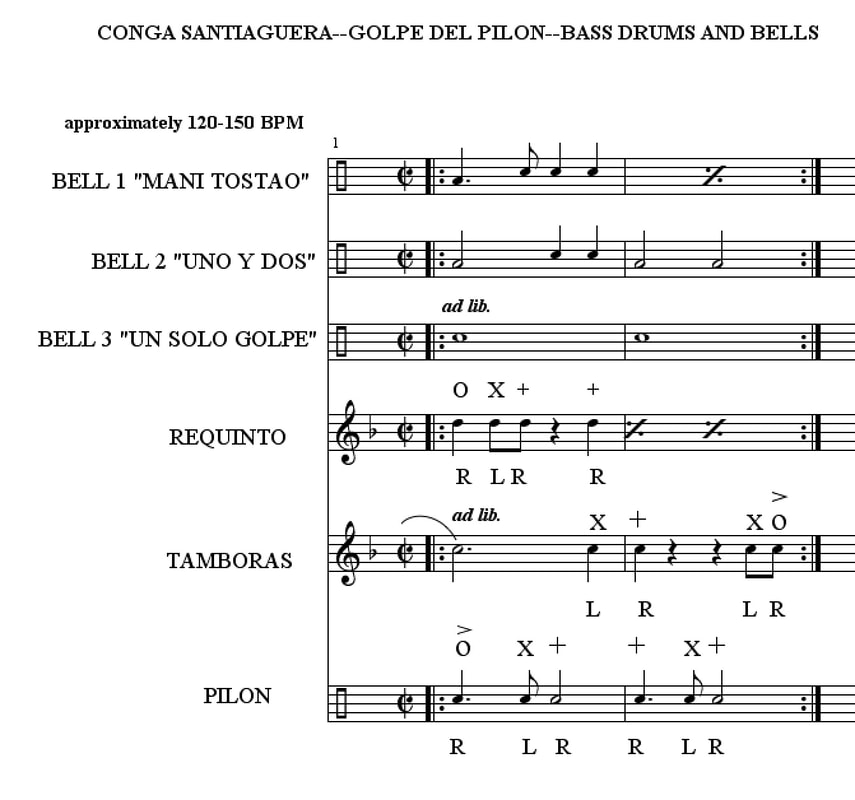

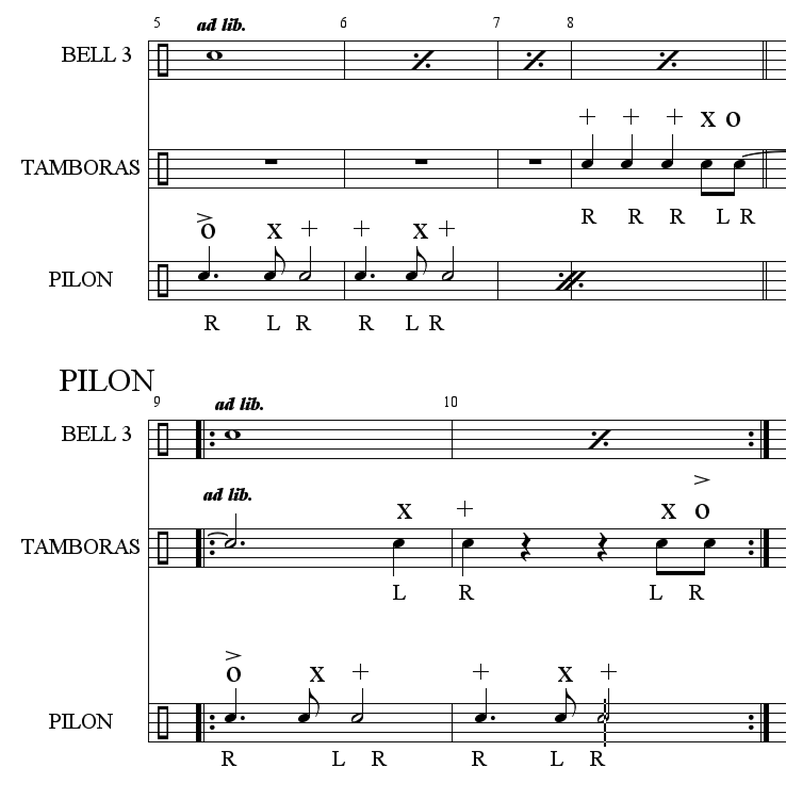

A more detailed description and transcription of the Pilón can be found in this blog post. In the Pilón rhythm, the quinto and the un solo golpe bell improvise; the two tamboras take turns improvising (ad lib is indicated in the transcription)

I'm including a transcription [2] for right handed players here, using the following notation:

BASS DRUMS:

O = OPEN STROKE WITH STICK

+= CLOSED STROKE WITH STICK (LEFT HAND MUFFLING BOTTOM HEAD)

X = SLAP WITH LEFT HAND ON BOTTOM HEAD

BELLS:

Different pitches on staff approximate higher and lower pitched sounds on brake drum. Lower pitched sounds are slightly accented.

BOKUS:

O = TONE

> = SLAP

T= TIP (FINGERTIPS)

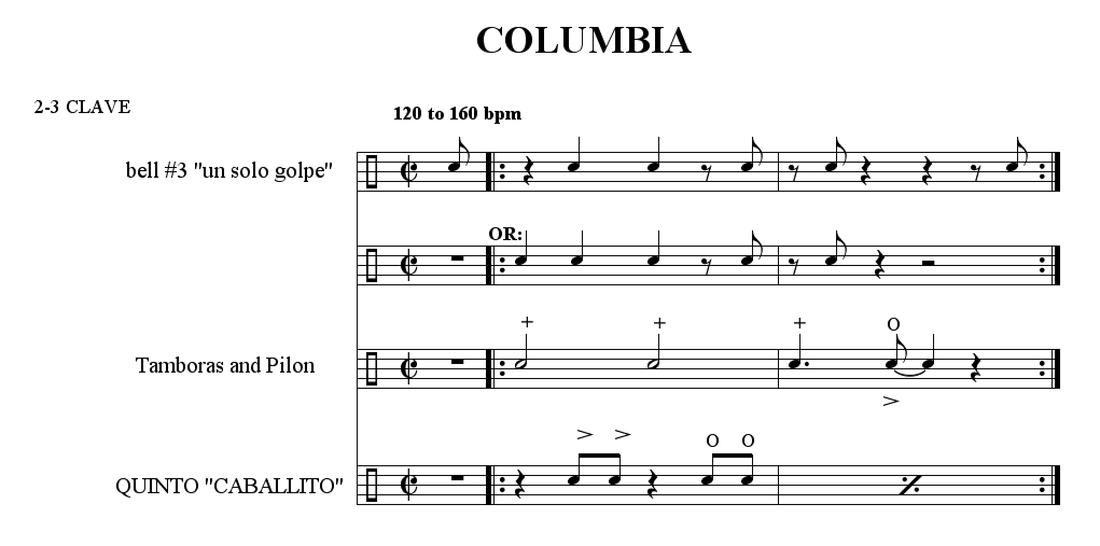

COLUMBIA

When listening to recordings of Conga, one occasionally hears the bass drums (pilon and two tamboras) briefly shift to a new groove. For example, if you listen to this recording, at 2:17 the bass drums seem to shift to a conga habanera pattern. In the context of the Conga, this is known as “El Golpe de La Columbia” or simply “Columbia” [3]. At 2:37, The bass drums switch to a new pattern known as “Masòn” before returning at 2:48 to “El Golpe del Pilón” or Pilón.

In Columbia and Masón, the only instruments whose patterns consistently differ from the Pilón rhythm are the “un solo golpe” bell, the Pilón, and the two Tamboras. The “un solo golpe” bell player has two different patterns to choose from; generally this player maintains the same pattern throughout the Columbia.

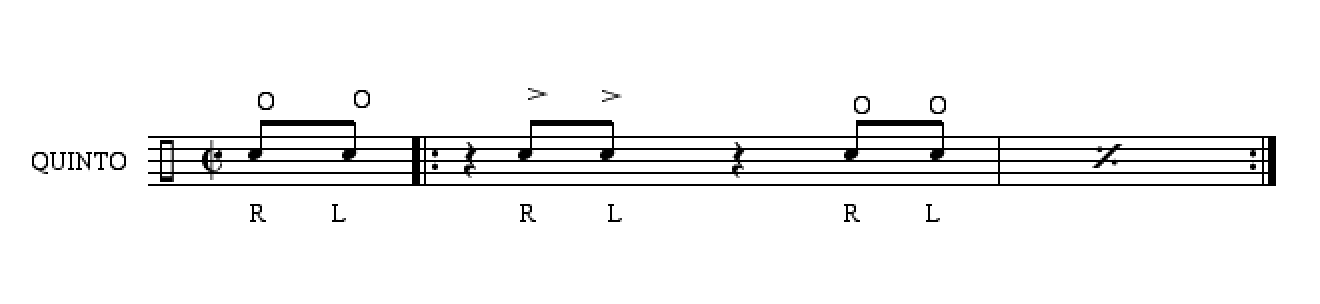

The Quinto usually plays the “caballito” pattern (shown here) during the Columbia; sometimes it continues to improvise.

The requinto, most of the bokuses, and the “mani tostao” and “uno y dos” bells maintain the same pattern for Pilon, Columbia and Masón.

This pattern as notated implies a 2-3 clave .

Note that the first bell pattern shown begins just before the downbeat and then repeats a two measure cycle. This will be described further in the section on transitions.

When listening to recordings of Conga, one occasionally hears the bass drums (pilon and two tamboras) briefly shift to a new groove. For example, if you listen to this recording, at 2:17 the bass drums seem to shift to a conga habanera pattern. In the context of the Conga, this is known as “El Golpe de La Columbia” or simply “Columbia” [3]. At 2:37, The bass drums switch to a new pattern known as “Masòn” before returning at 2:48 to “El Golpe del Pilón” or Pilón.

In Columbia and Masón, the only instruments whose patterns consistently differ from the Pilón rhythm are the “un solo golpe” bell, the Pilón, and the two Tamboras. The “un solo golpe” bell player has two different patterns to choose from; generally this player maintains the same pattern throughout the Columbia.

The Quinto usually plays the “caballito” pattern (shown here) during the Columbia; sometimes it continues to improvise.

The requinto, most of the bokuses, and the “mani tostao” and “uno y dos” bells maintain the same pattern for Pilon, Columbia and Masón.

This pattern as notated implies a 2-3 clave .

Note that the first bell pattern shown begins just before the downbeat and then repeats a two measure cycle. This will be described further in the section on transitions.

MASÓN

The masón rhythm of the conga is related to the masón of the tumba francesa; this will be discussed in the section on origins.

During a performance of the Pilón-Columbia-Masón “cycle,” the masón rhythm is played immediately after the Columbia. As in the Columbia, only the

“un solo golpe” bell, the Pilón and the two Tamboras change their patterns. The Pilón and tambora pattern is adapted directly from the masón of the tumba francesa, which uses a small tambora or “tamborita.”

The masón rhythm of the conga is related to the masón of the tumba francesa; this will be discussed in the section on origins.

During a performance of the Pilón-Columbia-Masón “cycle,” the masón rhythm is played immediately after the Columbia. As in the Columbia, only the

“un solo golpe” bell, the Pilón and the two Tamboras change their patterns. The Pilón and tambora pattern is adapted directly from the masón of the tumba francesa, which uses a small tambora or “tamborita.”

Recently, La Conga de Los Hoyos and Conga Paso Franco [4] have changed their quinto patterns for the Mason rhythm, but this practice is not nearly as standardized as the use of the caballito pattern for the Columbia. The quinto pattern they play is based on the “quijá” pattern from the tajona, a genre closely related to the tumba Francesa. Shown here is one of a few versions of this pattern that i observed:

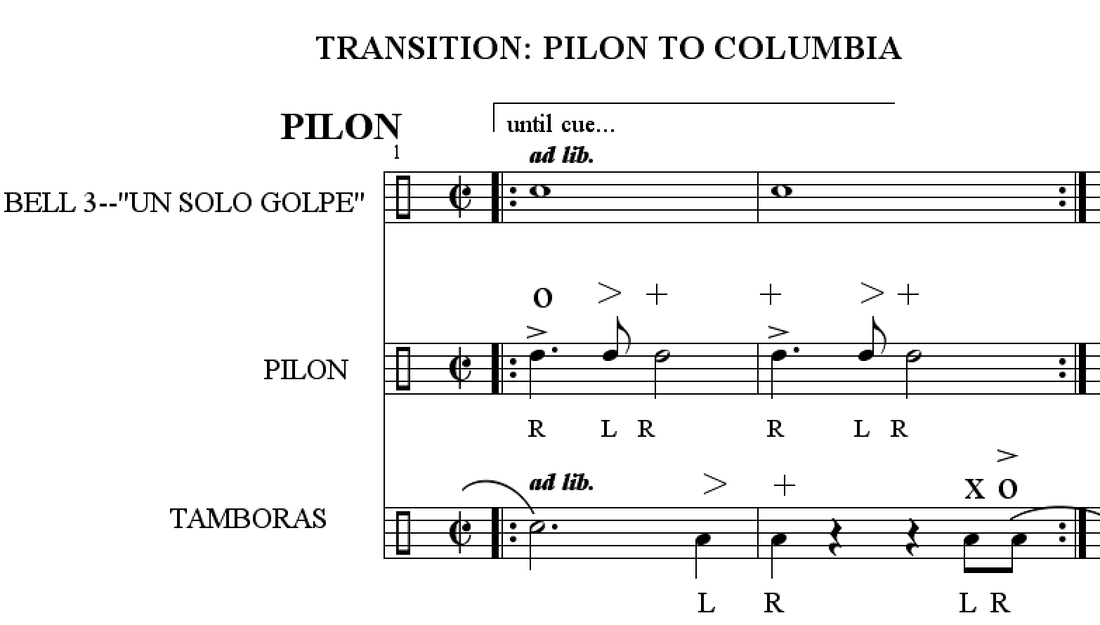

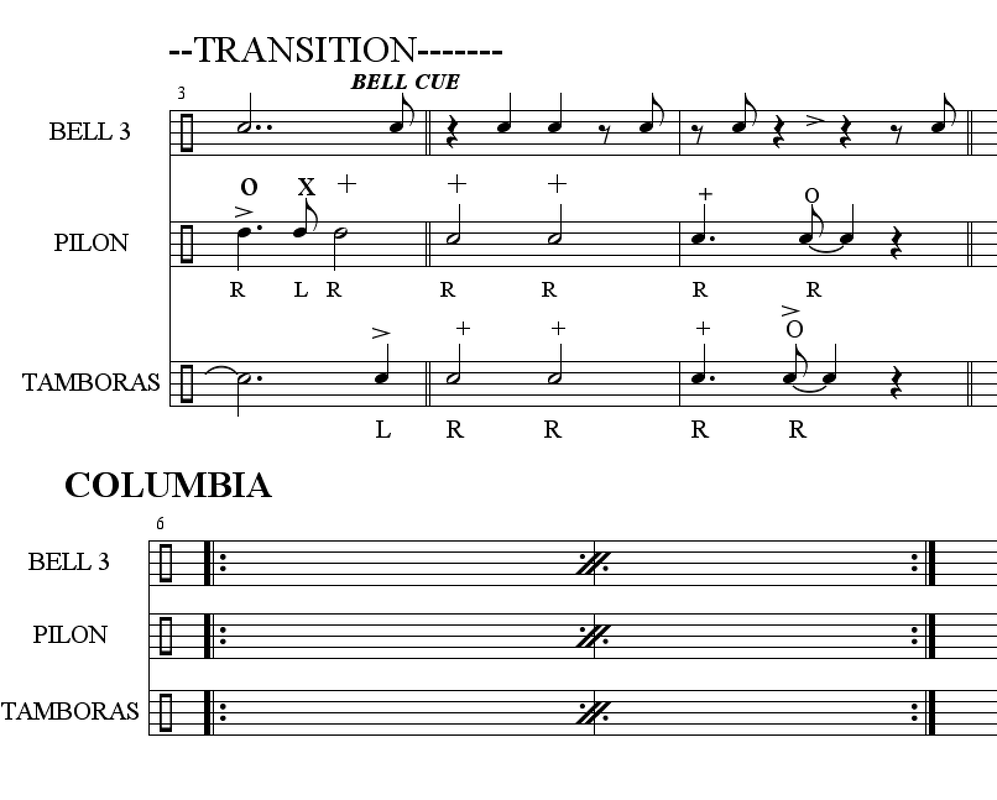

Transition: Pilon to Columbia

This transition is signaled by the “un solo golpe” bell player.

The Pilon, Tambora and quinto players must be alert and ready to respond to this call.

This transition is signaled by the “un solo golpe” bell player.

The Pilon, Tambora and quinto players must be alert and ready to respond to this call.

For the quinto, the transition to caballito occurs on beat 4:

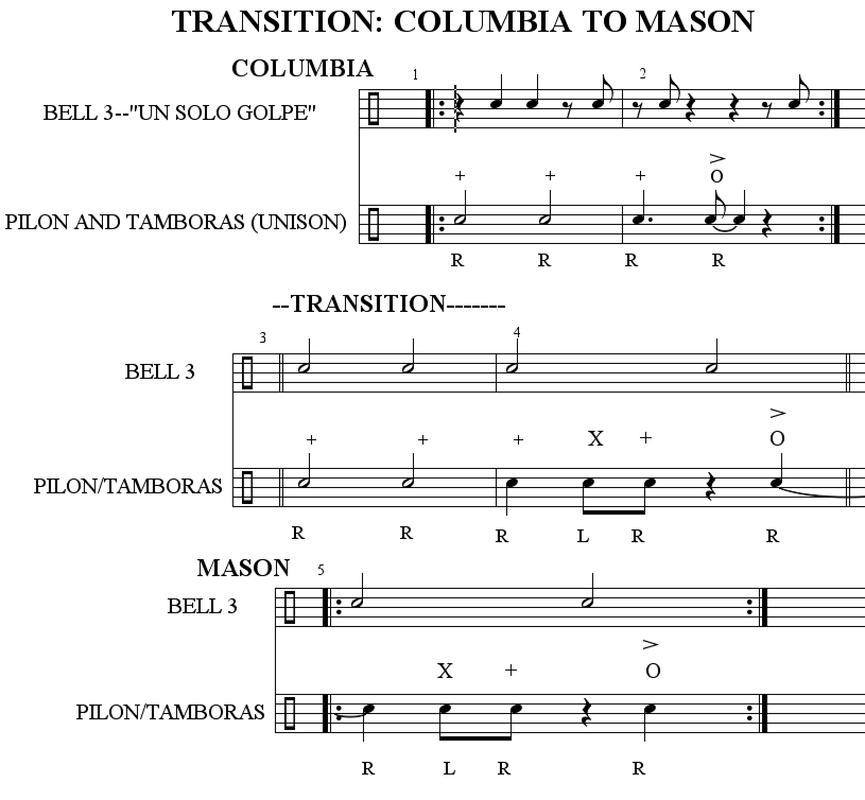

Transition : Columbia to Masón

The transition from Columbia to Mason is signaled by the “un solo golpe” bell player. This player will switch from the syncopated columbia pattern to the much more “straight” Mason pattern:

The transition from Columbia to Mason is signaled by the “un solo golpe” bell player. This player will switch from the syncopated columbia pattern to the much more “straight” Mason pattern:

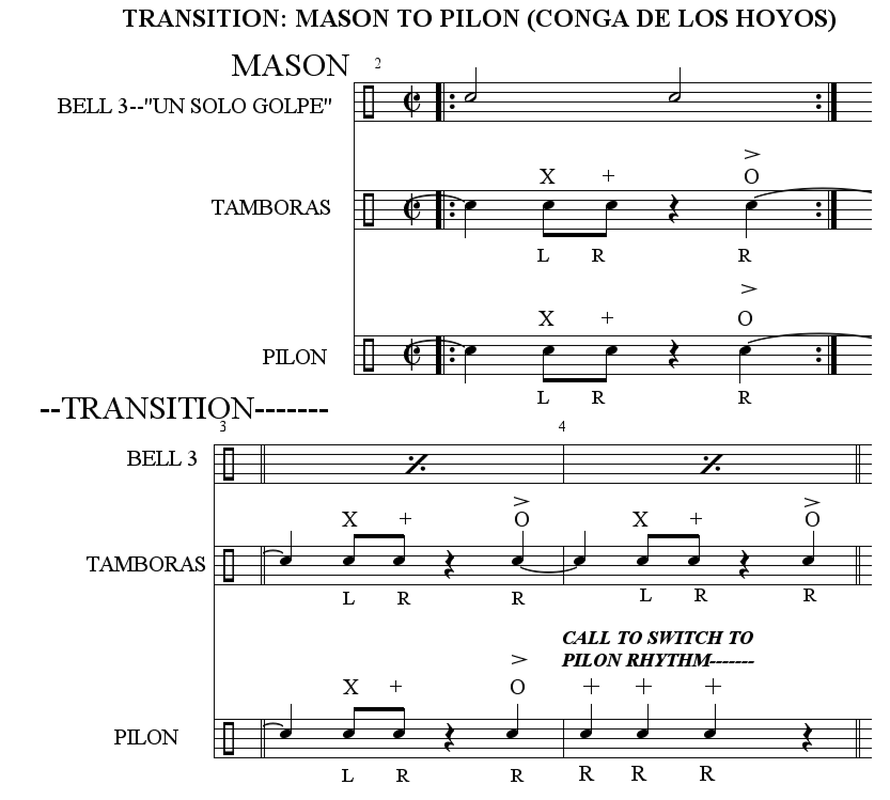

Transition : Mason to pilon

Of the three transitions, the change from Mason back to Pilon seems to be least standardized and consistent. In my studies I've seen a few different versions of this transition. Because La Conga de Los Hoyos is the Conga whose music I'm most familiar with, I will start with their current transition, as explained to me by musical director Lazaro Bandera Malet during private classes in June 2019.

According to Lazaro the Pilon drum calls the transition back to the Pilon rhythm by playing the following phrase on the “two side” of the clave:

Of the three transitions, the change from Mason back to Pilon seems to be least standardized and consistent. In my studies I've seen a few different versions of this transition. Because La Conga de Los Hoyos is the Conga whose music I'm most familiar with, I will start with their current transition, as explained to me by musical director Lazaro Bandera Malet during private classes in June 2019.

According to Lazaro the Pilon drum calls the transition back to the Pilon rhythm by playing the following phrase on the “two side” of the clave:

The tamboras sometimes respond a few measures later with the following phrase (also on the “two side” of the clave) to signal their transition back to the Pilon rhythm:

The entire transition would look like this:

In Conga Paso Franco, the quinto signals the transition from Masón to Pilón.

This “call” is essentially the same phrase that the quinto plays at the beginning of a performance after the corneta china plays its call:

This “call” is essentially the same phrase that the quinto plays at the beginning of a performance after the corneta china plays its call:

I'll note here that the Masón to Pilón transitions transcribed here are based on my lessons with Lazaro and Kiki. I've observed slightly different transitions when watching these two congas rehearse.

Origins and performance practice -- Pilon

The Pilon rhythm is generally agreed to have originated in La Conga de Los Hoyos, Santiago's oldest [5] and most famous and influential conga. Mililián Galis Riveri “Galí” [6] cites the influence of gagá (rara), a genre from Haiti, in the creation of this rhythm when it debuted in 1914. I would agree that the overall feel of Pilon is very similar to that of rara, but I am not aware of any research directly linking the two [7].

The conga santiaguera’s characteristic syncopated tambora accent (just before the downbeat) is believed to have been created by “Nanano”, a musician from Los Hoyos, in the 1930s. A few years later “Pililí” (also from Los Hoyos) began to improvise on the tambora.

Origins and performance practice --Columbia

The Columbia definitely resembles the Conga Habanera (a.k.a “comparsa” rhythm) due to its strong bass drum accent on the “and” of beat two on the “three-side” of the clave.

Gali attributes the Columbia to the influence of the conga rhythm as played in Havana and Matanzas in the early 1900s. According to Gali, ex-soldiers from Matanzas taught other musicians in the Tívoli neighborhood of Santiago to play Columbia (based on conga Habanera or Matancera style In 1913. La Conga del Tivoli debuted in that year’s carnival playing this rhythm [8].

The name “Columbia “ has at least two possible sources: a military camp in Havana, where some Santiagueros were stationed, or a railroad station in the province of Matanzas. This rhythm is not directly related to the rumba columbia. In my class with Bandera, he stated that the “un solo golpe” bell pattern for Columbia originated in La Conga de Los Hoyos and is derived from the 12/8 bell pattern used in rumba columbia.

Many informants have also stated that the Columbia is played while climbing hills during parades. Columbia and mason are also performed while the conga is stationary; Los Hoyos traditionally plays Columbia and Masón near the end of a parade when they are close to their foco cultural (headquarters).

Origins and performance practice -- Masón

According to Galí, the first use of the Golpe del mason in the Conga is generally believed to have been in 1936 [9]. Gali stated to me that “Nanano,” tambora player of Los Hoyos was the first to adapt this pattern to the conga context.

The mason pattern as played on the Pilon and Tamboras in the conga is the the only consistent musical link to the tumba francesa; as stated above, Bandera has recently started to change the quinto (and some boku) patterns in Los Hoyos to more definitivelty “declare” a mason rhythm [10].

Conclusions

There is little dispute that the Pilon and Mason rhythms originated in La Conga de Los Hoyos and that the Columbia rhythm originated in La Conga del Tívolí.

At this point it is not clear whether all eight congas in Santiago consistently include the Pilón -Columbia -Mason cycle in their perfomances. In my 2019 visit to santiago I saw Los Hoyos and Paso Franco play the full three part cycle. I saw el Guayabito and San Agustin play the Columbia but not the Mason.

It seems that the tradition of playing this cycle originated with, and continues to be strongest in, La Conga de Los Hoyos . From my brief observation, Los Hoyos seemed to have the most consistent and organized transition. I also confirmed with Bandera that Los Hoyos always plays columbia and mason when they parade. It's hard to say whether the other Congas consistently play this cycle.

I'd argue that the Columbia and Mason rhythms are performed mainly as a way of maintaining tradition. The Pilon rhythm is played for the vast majority of any parade or performance. When listening to recordings, the Columbia is easier to recognize than the Masón because of its strong bass drum accent. Columbia and Mason are usually played for around a minute (or less) each, making it sometimes difficult to dístinguish hem.

NOTES:

[1] Not to be confused with the Pilón dance rhythm popularized by Pancho Alonso in the 1960s. There is, however, a little known connection between between the “Pilón” of the conga and the “Pilón” of popular music: the drummer Esmerido "Loló" Ferrera. For more info see: https://www.ritmacuba.com/pilon.html (in French).

[2] The patterns shown here are the most common ones used by the various Congas in Santiago. There are, of course, variants; for example, the Conga de Los Hoyos has its own slightly different patterns for the requinto drum and the “uno y dos” bell. My main sources for the patterns transcribed are Lazaro Bandera, musical director of Los Hoyos, and Richard Leonel “Kiki” Ferrera, musical director of Conga Paso Franco. Also note that the un solo golpe and tambora patterns shown here are points of departure for improvisation.

Also, as with most music from the African diaspora, transcriptions cannot adequately represent the sound and feel of the style. Repeated listening, study, and observation is necessary to play this music.

[3] Not to be confused with Rumba Columbia which is generally believed to be from Matanzas province.

[4] Based on 2019 interviews with musical directors of these two Congas.

[5] While many point to La Conga del Tivoli as the “first” conga in Santiago, most santiagueros refer to La Conga de Los Hoyos as the oldest and “most traditional” conga and cite a founding date of 1902. Part of this dispute, in my opinion, depends on how we define “conga.” There is little doubt in my mind that Los Hoyos is the oldest continuously existing conga. La Conga del Tívoli disbanded in 1939. More on this in another post...

[6] Gali’s book “La percusión en los ritmos afrocubanos

y haitiano-cubanos" is, to my knowledge, the most in-depth source of written information about the music, history and origins of the conga santiaguera; it is the main source for my discussion of the origins of Pilon, Columbia and masón.

[7] It is also hard to say whether gagá was actually performed in Cuba in 1914. More research is needed.

[8] See footnote 6

[9] https://www.cndenglish.com/index.php/en/noticia/conga-los-hoyos-pride-santiago

Claims an origin date of 1938.

[10] Lesson/interview with Lazaro Bandera, June 2019

Acknowledgements and Sources

Thanks to:

Felix Bandera, director of La Conga de Los Hoyos, and Lazaro Bandera Malet, musical director, for generously sharing their extensive knowledge of this tradition.

Richard Leonel “Kiki” Ferrera, musical director, and all the members of Conga Paso Franco for sharing their knowledge.

Raul Lopez Martinez, director of Conga San Agustín, for his warm welcome and detailed explanations of his Conga’s style.

Daniel Chatelain of http:www.ritmacuba.com/ for sharing incredible amounts of information, both on his website and via email.

Galis Riveri, Mililián “Galí,” for clearing up a few doubts I had about material in his incredible book.

Lani Milstein for sharing information via email. Her excellent and very detailed thesis includes her own transcriptions of Pilon, Mason and Columbia.

Lani also wrote this excellent article which helped inspire me to quit procrastinating and go to Santiago!

The transcriptions included here are based on my own private lessons with Lazaro Bandera and other teachers in Santiago, and repeated viewings of this video.

Recordings and videos

"El Toque de Los Hoyos": an excellent demonstration of Pilón, Columbia and Masón by Lazaro Banderas and musicians from Los Hoyos.

A few relevant playlists:

CONGA SANTIAGUERA--GOOD RECORDINGS

CONGA SANTIAGUERA- “CYCLE”--PILON, COLUMBIA, AND MASÓN

Documentary: "Se Llama Conga"

Other links:

Lani Milsteins article

Article about Conga de Los Hoyos

https://www.bluethroatproductions.com/video/conga-series

Ritmacuba article (in french) about the instruments of the conga. Ritmacuba.com is a great resource.

BOOKS:

Mililián Galis Riveri “Galí”.

La percusión en los ritmos afrocubanos y haitiano-cubanos. Santiago de Cuba: Ediciones Caserón, 2015. Print;

includes transcriptions and history of conga santiaguera dating back to 1913.

Millet, José, Rafael Brea, and Manuel Ruiz Vila.

Barrio, Comparsa y Carnaval Santiaguero. Santo Domingo: Ediciones Casa del Caribe, 1997. Print.

An in depth study of the Los Hoyos neighborhood in Santiago and its conga. Interviews with key members of La Conga de Los Hoyos and evidence of the importance of carnival and conga to the culture and history of Santiago.

2 Comments

Author

Nick Herman is a New York-based percussionist, educator, composer and arranger.

Archives

May 2023

July 2020

May 2020

March 2020

December 2019

RSS Feed

RSS Feed